National Gallery

| National Gallery | |

|---|---|

|

|

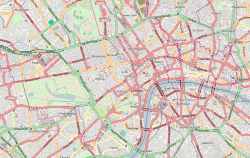

Location within Central London

|

|

| Established | 1824 |

| Location | Trafalgar Square, London WC2, England, United Kingdom |

| Visitor figures |

4,780,030 (2009)[1]

|

| Director | Nicholas Penny |

| Public transit access | Charing Cross Embankment Leicester Square |

| Website | www.nationalgallery.org.uk |

The National Gallery in London was founded in 1824 and houses a rich collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900[a] in its home on Trafalgar Square. The gallery is an exempt charity, and a non-departmental public body of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport.[2] Its collection belongs to the public of the United Kingdom and entry to the main collection (though not some special exhibitions) is free of charge.

Unlike comparable art museums such as the Louvre in Paris or the Museo del Prado in Madrid, the National Gallery was not formed by nationalising an existing royal or princely art collection. It came into being when the British government bought 36 paintings from the heirs of the insurance broker and patron of the arts John Julius Angerstein in 1824. After that initial purchase the Gallery was shaped mainly by its early directors, notably Sir Charles Lock Eastlake, and by private donations, which comprise two thirds of the collection.[3] The resulting collection is small in size, compared with many European national galleries, but encyclopaedic in scope; most major developments in Western painting "from Giotto to Cézanne"[4] are represented with important works. It used to be claimed that this was one of the few national galleries that had all its works on permanent exhibition,[5] but this is no longer the case.

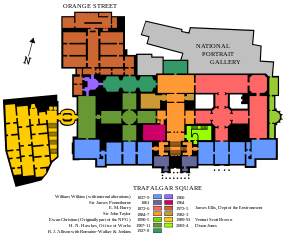

The present building, the third to house the National Gallery, was designed by William Wilkins from 1832–8. Only the façade onto Trafalgar Square remains essentially unchanged from this time, as the building has been expanded piecemeal throughout its history. The building often came under fire for its perceived aesthetic deficiencies and lack of space; the latter problem led to the establishment of the Tate Gallery for British art in 1897. The Sainsbury Wing, an extension to the west by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, is a notable example of Postmodernist architecture in Britain. The current Director of the National Gallery is Nicholas Penny.

Contents |

History

The call for a National Gallery

The late 18th century saw the nationalisation of royal or princely art collections across mainland Europe. The Bavarian royal collection (now in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich) opened to the public in 1779, that of the Medici in Florence around 1789 (as the Uffizi Gallery), and the Museum Français at the Louvre was formed out of the former French royal collection in 1793.[6] Great Britain, however, did not emulate the continental model, and the British Royal Collection remains in the sovereign's possession today. In 1777 the British government had the opportunity to buy an art collection of international stature, when the descendants of Sir Robert Walpole put his collection up for sale. The MP John Wilkes argued for the government to buy this "invaluable treasure" and suggested that it be housed in "a noble gallery... to be built in the spacious garden of the British Museum"[7] Nothing came of Wilkes's appeal and 20 years later the collection was bought in its entirety by Catherine the Great; it is now to be found in the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.

A plan to acquire 150 paintings from the Orléans collection, which had been brought to London for sale in 1798, also failed, despite the interest of both the King and the Prime Minister, Pitt the Younger.[8] The twenty-five paintings from that collection now in the Gallery, including "NG1", have arrived by a variety of routes. In 1799 the dealer Noel Desenfans offered a ready-made national collection to the British government; he and his partner Sir Francis Bourgeois had assembled it for the king of Poland, before the Third Partition in 1795 abolished Polish independence.[6] This offer was declined and Bourgeois bequeathed the collection to his old school, Dulwich College, on his death. The collection opened in Britain's first purpose-built public gallery, the Dulwich Picture Gallery, in 1814. The Scottish dealer William Buchanan and another collector, Joseph Count Truchsess, both formed art collections expressly as the basis for a future national collection, but their respective offers (made in the same year, 1803) were also declined.[6]

Following the Walpole sale many artists, including James Barry and John Flaxman, had made renewed calls for the establishment of a National Gallery, arguing that a British school of painting could only flourish if it had access to the canon of European painting. The British Institution, founded in 1805 by a group of aristocratic connoisseurs, attempted to address this situation. The members lent works to exhibitions that changed annually, while an art school was held in the summer months. However, as the paintings that were lent were often mediocre,[9] some artists resented the Institution and saw it as a racket for the gentry to increase the sale prices of their Old Master paintings.[10] One of the Institution's founding members, Sir George Beaumont, Bt, would eventually play a major role in the National Gallery's foundation by offering a gift of 16 paintings.

In 1823 another major art collection came on the market, which had been assembled by the recently deceased John Julius Angerstein. Angerstein was a Russian-born émigré banker based in London; his collection numbered 38 paintings, including works by Raphael and Hogarth's Marriage à-la-mode series. On July 1, 1823 George Agar Ellis, a Whig politician, proposed to the House of Commons that it purchase the collection.[11] The appeal was given added impetus by Beaumont's offer, which came with two conditions: that the government buy Angerstein's collection, and that a suitable building was to be found. The unexpected repayment of a war debt by Austria finally moved the government to buy Angerstein's collection, for £57,000.

Foundation and early history

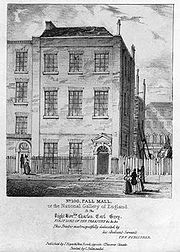

The National Gallery opened to the public on 10 May 1824, housed in Angerstein's former townhouse on No. 100 Pall Mall. Angerstein's paintings were joined in 1826 by those from Beaumont's collection, and in 1828 by the Reverend William Holwell Carr's bequest of 34 paintings. Initially the Keeper of Paintings, William Seguier, bore the burden of managing the Gallery, but in July 1824 some of this responsibility fell to the newly formed board of trustees.

The National Gallery at Pall Mall was frequently overcrowded and hot and its diminutive size in comparison with the Louvre in Paris was the cause of national embarrassment. But Agar Ellis, now a trustee of the Gallery, appraised the site for being "in the very gangway of London"; this was seen as necessary for the Gallery to fulfil its social purpose.[12] Subsidence in No. 100 caused the Gallery to move briefly to No. 105 Pall Mall, which the novelist Anthony Trollope described as a "dingy, dull, narrow house, ill-adapted for the exhibition of the treasures it held".[12] This in turn had to be demolished for the opening of a road to Carlton House Terrace.[13]

In 1832 construction began on a new building by William Wilkins on the site of the King's Mews in Charing Cross, in an area that had been transformed over the 1820s into Trafalgar Square. The location was a significant one, between the wealthy West End and poorer areas to the east.[14] The argument that the collection could be accessed by people of all social classes outstripped other concerns, such as the pollution of central London or the failings of Wilkins's building, when the prospect of a move to South Kensington was mooted in the 1850s. According to the Parliamentary Commission of 1857, "The existence of the pictures is not the end purpose of the collection, but the means only to give the people an ennobling enjoyment".[15]

Growth under Eastlake and his successors

15th- and 16th-century Italian paintings were at the core of the National Gallery and for the first 30 years of its existence the Trustees' independent acquisitions were mainly limited to works by High Renaissance masters. Their conservative tastes resulted in several missed opportunities and the management of the Gallery later fell into complete disarray, with no acquisitions being made between 1847 and 1850.[16] A critical House of Commons Report in 1851 called for the appointment of a director, whose authority would surpass that of the trustees. Many thought the position would go to the German art historian Gustav Friedrich Waagen, whom the Gallery had consulted on previous occasions about the lighting and display of the collections. However, the man preferred for the job by Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the Prime Minister, Lord Russell, was the Keeper of Paintings at the Gallery, Sir Charles Lock Eastlake.

_01.jpg)

The new director's taste was for the Northern and Early Italian Renaissance masters or "primitives", who had been neglected by the Gallery's acquisitions policy but were slowly gaining recognition from connoisseurs. Eastlake made annual tours to the continent and to Italy in particular, seeking out appropriate paintings to buy for the Gallery. In all, he bought 148 pictures abroad and 46 in Britain,[17] among the former such seminal works as Paolo Uccello's Battle of San Romano. Eastlake also amassed a private art collection during this period, consisting of paintings that he knew did not interest the trustees. His ultimate aim, however, was for them to enter the National Gallery; this was duly arranged upon his death by his friend and successor as director, William Boxall, and his widow Lady Eastlake.

The Gallery's lack of space remained acute in this period. In 1845 a large bequest of British paintings was made by Robert Vernon; there was insufficient room in the Wilkins building so these were displayed first in Vernon's townhouse, 50 Pall Mall, and then at Marlborough House.[18] The Gallery was even less well equipped for its next major bequest: over 1,000 works by J. M. W. Turner, which he had left to the nation on his death in 1856.[19] These were displayed off-site in South Kensington, where they were joined by the Vernon collection. This set a precedent for the display of British art on a different site, which eventually resulted in the creation of the National Gallery of British Art (the Tate Gallery) in 1897. Works by artists born after 1790 were moved to the new gallery on Millbank, which allowed Hogarth, Turner and Constable to remain in Trafalgar Square. Turner's request that his paintings be displayed alongside those of Claude is still honoured in Room 15 of the Gallery, but his bequest has never been adequately displayed in its entirety; today the works are divided between Trafalgar Square and the Clore Gallery, a small purpose-built extension to the Tate completed in 1985.

The third director, Sir Frederick William Burton, laid the foundations of the collection of 18th-century art and made several outstanding purchases from English private collections, including The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger.

The early 20th century

The agricultural crisis at the turn of the 20th century caused many aristocratic families to sell their paintings, but the British national collections were priced out of the market by American plutocrats.[20] This prompted the foundation of the National Art Collections Fund, a society of subscribers dedicated to stemming the flow of artworks to the United States. Their first acquisition for the National Gallery was Velázquez's Rokeby Venus in 1906, followed by Holbein's Portrait of Christina of Denmark in 1909. However, despite the crisis in aristocratic fortunes, the following decade was one of several great bequests from private collectors. In 1909 the industrialist Dr Ludwig Mond gave 42 Italian renaissance paintings, including the Mond Crucifixion by Raphael, to the Gallery.[21] Other bequests of note were those of George Salting in 1910, Austen Henry Layard in 1916 and Sir Hugh Lane in 1917; the last of these was one of the Gallery's more controversial bequests. Lane died on board the RMS Lusitania in 1915, and an early version of his will left 39 paintings, including Renoir's Umbrellas, to the National Gallery unless a suitable building could be built in Dublin; later he amended it with a codicil that the works should only go to Ireland, but this was never witnessed.[22] A dispute began which was not resolved until 1959;[23] part of the collection is now on permanent loan to Dublin City Gallery ("The Hugh Lane") and other works rotate between London and Dublin every few years.

In a rare example of the political protest for which Trafalgar Square is famous occurring in the National Gallery, the Rokeby Venus was damaged on 10 March 1914 by Mary Richardson, a campaigner for women's suffrage, in protest against the arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst the previous day. Later that month another suffragette attacked five Bellinis, causing the Gallery to close until the start of the First World War, when the Women's Social and Political Union called for an end to violent acts drawing attention to their plight.[24]

During the 19th century the National Gallery contained no works by a contemporary artist, but this situation was belatedly amended by Sir Hugh Lane's bequest of Impressionist paintings in 1917. A fund for the purchase of modern paintings established by Samuel Courtauld in 1923 bought Seurat's Bathers at Asnières and other notable modern works for the nation;[25] in 1934 these transferred to the National Gallery from the Tate.

The Gallery in World War II

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II the paintings were evacuated to various locations in Wales, including Penrhyn Castle and the university colleges of Bangor and Aberystwyth.[26] In 1940, as the Battle of France raged, a more secure home was sought, and there were discussions about moving the paintings to Canada. This idea was firmly rejected by Winston Churchill, who wrote in a telegram to the director Kenneth Clark, “bury them in caves or in cellars, but not a picture shall leave these islands”.[27] Instead a slate quarry at Manod, near Blaenau Ffestiniog in North Wales, was requisitioned for the Gallery's use. In the seclusion afforded by the paintings' new location, the Keeper (and future director) Martin Davies began to compile scholarly catalogues on the collection, helped by the fact that the Gallery's library was also stored in the quarry. The move to Manod confirmed the importance of storing paintings at a constant temperature and humidity, something the Gallery's conservators had long suspected but had hitherto been unable to prove.[28] This eventually resulted in the first air-conditioned gallery opening in 1949.[18]

For the course of the war Myra Hess gave daily recitals in the empty building, to raise public morale at a time when every concert hall in London was closed.[29] Exhibitions of work by war artists, including Paul Nash, Henry Moore and Stanley Spencer, were held from 1940; the War Artists' Advisory Committee had been set up by Clark in order "to keep artists at work on any pretext".[30] In 1941 a request from an artist to see Rembrandt's Portrait of Margaretha de Geer (a new acquisition) resulted in the "Picture of the Month" scheme, in which a single painting was removed from Manod and exhibited to the general public in the National Gallery each month. The art critic Herbert Read, writing that year, called the National Gallery "a defiant outpost of culture right in the middle of a bombed and shattered metropolis".[31] The paintings returned to Trafalgar Square in 1945.

Post-war developments

In the post-war years acquisitions have become increasingly difficult for the National Gallery as the prices for Old Masters – and even more so for the Impressionists and Post-impressionists – have risen beyond its means. Some of the Gallery's most remarkable purchases in this period would have been impossible without the major public appeals backing them, including The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist by Leonardo da Vinci (bought in 1962), Titian’s Death of Actaeon (1972). The Gallery's purchase grant from the government was frozen in 1985, but later that year it received an endowment of £50 million from Sir Paul Getty, enabling many major purchases to be made.[18] Ironically, the institution that posed the biggest threat to the Gallery's acquisitions policy was (and remains) the extremely well-endowed J. Paul Getty Museum in California, established by Getty's estranged father. Also in 1985 Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover and his brothers, the Hon. Simon Sainsbury and Sir Timothy Sainsbury, made a donation that enabled the construction of the Sainsbury Wing.

The directorship of Neil MacGregor saw a major rehang at the Gallery, dispensing with the classification of paintings by national school that had been introduced by Eastlake. The new chronological hang sought to emphasise the interaction between cultures rather than fixed national characteristics, reflecting the change in art historical values since the 19th century. In other respects, however, Victorian tastes were rehabilitated: the building's interiors were no longer considered an embarrassment and were restored, and in 1999 the Gallery accepted a bequest of 26 Italian Baroque paintings from Sir Denis Mahon. Earlier in the 20th century many considered the Baroque to be beyond the pale: in 1945 the Gallery's trustees declined to buy a Guercino from Mahon's collection for £200. The same painting was valued at £4 m in 2003.[32] Mahon's bequest was made on the condition that the Gallery would never deaccession any of its paintings or charge for admission.[33]

The respective remits of the National and Tate Galleries, which had long been contested by the two institutions, were more clearly defined in 1996. 1900 was established as the cut-off point for paintings in the National Gallery, and in 1997 more than 60 post-1900 paintings from the collection were given to the Tate on a long-term loan, in return for works by Gauguin and others. However, future expansion of the National Gallery may yet see the return of 20th-century paintings to its walls.[34]

In the 21st century there have been two large fundraising campaigns at the Gallery: in 2004, to buy Raphael’s Madonna of the Pinks, and in 2008, for Titian's Diana and Actaeon. Diana and Actaeon was bought in tandem with the National Gallery of Scotland for £50 m. The two galleries will attempt to buy the pendant piece to the Titian, Diana and Callisto, from the collection of the Duke of Sutherland by 2012. The National Gallery is now largely priced out of the market for Old Master paintings and can only make such acquisitions with the backing of major public appeals; the departing director Charles Saumarez Smith expressed his frustration at this situation in 2007.[35]

The building

|

William Wilkins's building

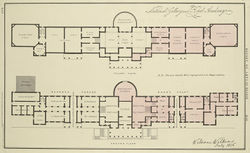

The first suggestion for a National Gallery on Trafalgar Square came from John Nash, who envisaged it on the site of the King's Mews, while a Parthenon-like building for the Royal Academy would occupy the centre of the square.[36] Economic recession prevented this scheme from being built, but a competition for the Mews site was eventually held in 1831, for which Nash submitted a design with C. R. Cockerell as his co-architect. Nash's popularity was waning by this time, however, and the commission was awarded to William Wilkins, who was involved in the selection of the site and submitted some drawings at the last moment.[37] Wilkins had hoped to build a "Temple of the Arts, nurturing contemporary art through historical example",[38] but the commission was blighted by parsimony and compromise, and the resulting building was deemed a failure on almost all counts.

The site only allowed for the building to be one room deep, as a workhouse and a barracks lay immediately behind.[b] To exacerbate matters, there was a public right of way through the site to these buildings, which accounts for the access porticoes on the eastern and western sides of the façade. These had to incorporate columns from the demolished Carlton House and their relative shortness result in an elevation that was deemed excessively low, and a far cry from the commanding focal point that was desired for the northern end of the Square. Also recycled are the sculptures on the façade, originally intended for Nash's Marble Arch but abandoned due to his financial problems.[c] The eastern half of the building housed the Royal Academy until 1868, which further diminished the space afforded to the Gallery.

The building was the object of public ridicule before it had even been completed, as a version of the design had been leaked to the Literary Gazette in 1833.[39] Two years before completion, its infamous "pepperpot" elevation appeared on the frontispiece of Contrasts (1836), an influential tract by the Gothicist A. W. N. Pugin, as an example of the degeneracy of the classical style.[40] Even William IV thought the building a "nasty little pokey hole",[41] while William Makepeace Thackeray called it "a little gin shop of a building".[36] The twentieth-century architectural historian Sir John Summerson echoed these early criticisms when he compared the arrangement of a dome and two diminutive turrets on the roofline to "the clock and vases on a mantelpiece, only less useful".[37] Sir Charles Barry's landscaping of Trafalgar Square, from 1840, included a north terrace so that the building would appear to be raised, thus addressing one of the points of complaint.[13] Opinion on the building had mellowed considerably by 1984, when the Prince of Wales called the Wilkins façade a "much-loved and elegant friend", in contrast to a proposed extension. (See below)

Alteration and expansion (Pennethorne, Barry and Taylor)

| New gallery (1860–1) by Sir James Pennethorne | |

The first significant alteration made to the building was the single, long gallery added by Sir James Pennethorne in 1860-1. Ornately decorated in comparison with the rooms by Wilkins, it nonetheless worsened the cramped conditions inside the building as it was built over the original entrance hall.[42] Unsurprisingly, several attempts were made either to completely remodel the National Gallery (as suggested by Sir Charles Barry in 1853), or to move it to more capacious premises in Kensington, where the air was also cleaner. In 1867 Barry’s son Edward Middleton Barry proposed to replace the Wilkins building with a massive classical building with four domes. The scheme was a failure and contemporary critics denounced the exterior as "a strong plagiarism upon St Paul's Cathedral".[43]

With the demolition of the workhouse, however, Barry was able to build the Gallery's first sequence of grand architectural spaces, from 1872 to 1876. Built to a polychrome Neo-Renaissance design, the Barry Rooms were arranged on a Greek cross-plan around a huge central octagon. Though it compensated for the underwhelming architecture of the Wilkins building, Barry's new wing was disliked by Gallery staff, who considered its monumental aspect to be in conflict with its function as exhibition space. Also, the decorative programme of the rooms did not take their intended contents into account; the ceiling of the 15th- and 16th-century Italian gallery, for instance, was inscribed with the names of British artists of the 19th century.[44] But despite these failures, the Barry Rooms provided the Gallery with a strong axial groundplan. This was to be followed by all subsequent additions to the Gallery for a century, resulting in a building of clear symmetry.

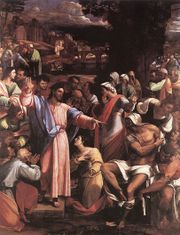

Pennethorne's gallery was demolished for the next phase of building, a scheme by Sir John Taylor extending northwards of the main entrance. Its glass-domed entrance vestibule had painted ceiling decorations by the Crace family firm, who had also worked on the Barry Rooms. A fresco intended for the south wall was never realised, and that space is now taken up by Frederic, Lord Leighton’s painting of Cimabue's Celebrated Madonna carried in Procession through the Streets of Florence (1853–5), lent by the Royal Collection in the 1990s.[45]

The 20th century: modernisation versus restoration

Later additions to the west came more steadily but maintained the coherence of the building by mirroring Barry’s cross-axis plan to the east. The use of dark marble for doorcases was also continued, giving the extensions a degree of internal consistency with the older rooms. The classical style was still in use at the National Gallery in 1929, when a Beaux-Arts style gallery was built, funded by the art dealer and Trustee Lord Duveen. However, it was not long before the 20th-century reaction against Victorian attitudes became manifest at the Gallery. From 1928 to 1952 the landing floors of Taylor's entrance hall were relaid with a new series of mosaics by Boris Anrep, who was friendly with the Bloomsbury Group. His mosaics at the National Gallery can be read as a satire on 19th-century conventions for the decoration of public buildings,[46] typified by the elaborate Frieze of Parnassus on the Albert Memorial. The central mosaic depicting The Awakening of the Muses includes portraits of Virginia Woolf and Greta Garbo, subverting the high moral tone of its Victorian forebears. In place of Christianity's seven virtues,[47] Anrep offered his own set of Modern Virtues, including "Humour" and "Open Mind"; the allegorical figures are again portraits of his contemporaries, including Winston Churchill, Bertrand Russell and T. S. Eliot.

In the 20th century the Gallery's late Victorian interiors fell out of favour with many commentators.[48] The Crace ceiling decorations in the entrance hall were not to the taste of the director Charles Holmes, and were obliterated by white paint.[49] The North Galleries, which opened to the public in 1975, marked the arrival of modernist architecture at the National Gallery. In the older rooms, the original classical details were effaced by partitions, daises and suspended roofs, the aim being to create neutral settings that did not distract from contemplation of the paintings themselves. But the Gallery's commitment to modernism was short-lived: by the 1980s Victorian style was no longer considered anathema, and a restoration programme began to restore the nineteenth and early 20th-century interiors to their purported original appearance. This began with the refurbishment of the Barry Rooms in 1985–86. From 1996 to 1999 even the North Galleries, by then considered to "lack a positive architectural character" were remodelled in a classical style, albeit a simplified one.[33]

The Sainsbury Wing and later additions

| Rejected "carbuncle" scheme by Ahrends, Burton and Koralek | |

The most important addition to the building in recent years has been the Sainsbury Wing, designed by the postmodernist architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown to house the collection of Renaissance paintings, and built in 1991. The building occupies the "Hampton's site" to the west of the main building, where a department store of the same name had stood until its destruction in the Blitz. The Gallery had long sought expansion into this space and in 1982 a competition was held to find a suitable architect; the shortlist included a radical high-tech proposal by Richard Rogers, among others. The design that won the most votes was by the firm Ahrends, Burton and Koralek, who then modified their proposal to include a tower, similar to that of the Rogers scheme. The proposal was dropped after the Prince of Wales compared the design to a "monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend",[50] The term "monstrous carbuncle", for a modern building that clashes with its surroundings, has since become commonplace.[51][52]

One of the conditions of the 1982 competition was that the new wing had to include commercial offices as well as public gallery space. However, in 1985 it became possible to devote the extension entirely to the Gallery's uses, due to a donation of almost £50 million from Lord Sainsbury and his brothers Simon and Sir Tim Sainsbury. A closed competition was held, and the schemes produced were noticeably more restrained than in the earlier competition.

In contrast with the rich ornamentation of the main building, the galleries in the Sainsbury Wing are pared-down and intimate, to suit the smaller scale of many of the paintings. The main inspirations for these rooms are Sir John Soane's toplit galleries for the Dulwich Picture Gallery and the church interiors of Filippo Brunelleschi (the stone dressing is in pietra serena, the grey stone local to Florence). The northernmost galleries align with Barry's central axis, so that there is a single vista down the whole length of the Gallery. This axis is exaggerated by the use of false perspective, as the columns flanking each opening gradually diminish in size until the visitor reaches the focal point of (as of 2009), an altarpiece by Cima of The Incredulity of St Thomas. Venturi's postmodernist approach to architecture is in full evidence at the Sainsbury Wing, with its stylistic quotations from buildings as disparate as the clubhouses on Pall Mall, the Scala Regia in the Vatican, Victorian warehouses and Ancient Egyptian temples.

Following the pedestrianisation of Trafalgar Square, the Gallery is currently engaged in a masterplan to convert the vacated office space on the ground floor into public space. The plan will also fill in disused courtyards and make use of land acquired from the adjoining National Portrait Gallery in St Martin's Place, which it gave to the National Gallery in exchange for land for its 2000 extension. The first phase, the East Wing Project designed by Jeremy Dixon and Edward Jones, opened to the public in 2004. This provided a new ground level entrance from Trafalgar Square, named in honour of Sir Paul Getty. The main entrance was also refurbished, and reopened in September 2005. Possible future projects include a "West Wing Project" roughly symmetrical with the East Wing Project, which would provide a future ground level entrance, and the public opening of some small rooms at the far eastern end of the building acquired as part of the swap with the National Portrait Gallery. This might include a new public staircase in the bow on the eastern façade. No timetable has been announced for these additional projects.

Controversies

One of the most persistent criticisms of the National Gallery, alongside the perceived inadequacies of the building, has been of its policy regarding the conservation of paintings. The Gallery's detractors accuse it of having an over-zealous approach to restoration and of turning a deaf ear to criticism. The first cleaning operation at the National Gallery began in 1844 after Eastlake's appointment as Keeper, and was the subject of attacks in the press after the first three paintings to receive the treatment – a Rubens, a Cuyp and a Velázquez – were unveiled to the public in 1846.[54] The Gallery's most virulent critic was J. Morris Moore, who wrote a series of letters to The Times under the pseudonym "Verax" savaging the institution's recent cleanings. While an 1853 Parliamentary Select Committee set up to investigate the matter cleared the Gallery of any wrongdoing, criticism of its methods has been erupting sporadically ever since from some in the art establishment.

The last major outcry against the use of radical conservation techniques at the National Gallery was in the immediate post-war years, following a restoration campaign by Chief Restorer Helmut Ruhemann while the paintings were in Manod Quarry. When the cleaned pictures were exhibited to the public in 1946 there followed a furore with parallels to that of a century earlier. The principal criticism was that the extensive removal of varnish, which was used in the 19th century to protect the surface of paintings but which darkened and discoloured them with time, may have resulted in the loss of "harmonising" glazes added to the paintings by the artists themselves. The opposition to Ruhemann's techniques was led by Ernst Gombrich, a professor at the Warburg Institute who in later correspondence with a restorer described being treated with "offensive superciliousness" by the National Gallery.[55] A 1947 commission concluded that no damage had been done in the recent cleanings, but some in conservation circles remain unhappy that the Gallery's attitude towards restoration has changed little since Ruhemann's time.

The National Gallery has also come under fire for misattributing paintings. Kenneth Clark's decision in 1939 to relabel a group of paintings by anonymous artists of the Venetian school as works by Giorgione, (a crowd-pulling artist due to the rarity of his paintings), caused outrage and made him deeply unpopular with his own staff, who locked him out of the library. More recently, the attribution of a 17th-century painting of Samson and Delilah (bought in 1980) to Rubens has been contested by a group of art historians, who believe that the National Gallery has not admitted the mistake to avoid embarrassing those who were involved in the purchase, many of whom still work for the Gallery.[56]

Collection highlights

|

Directors

Associate artists

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Micro Gallery, installed in 1991.

Notes

Footnotes

- a. ^ Sculptures and applied art are in the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum houses earlier art, non-Western art, prints and drawings, and art of a later date is at Tate Modern. Some British art is in the National Gallery, but the National Collection of British Art is mainly in Tate Britain.

- b. ^ St Martin's Workhouse (to the east) was cleared for the construction of E. M. Barry's extension, whereas St George's Barracks stayed until 1911, supposedly because of the need for troops to be at hand to quell disturbances in Trafalgar Square. (Conlin 2006, 401) Wilkins hoped for more land to the south, but was denied it as building there would have obscured the view of St Martin-in-the-Fields.

- c. ^ They are as follows: above the main entrance, a blank roundel (originally to feature the Duke of Wellington's face) flanked by two female figures (personifications of Europe and Asia/India, sites of his campaigns) and high up on the eastern façade, Minerva by John Flaxman, originally Britannia.

References

- ↑ "VISITS MADE IN 2009 TO VISITOR ATTRACTIONS IN MEMBERSHIP WITH ALVA". Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. http://www.alva.org.uk/visitor_statistics/. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ↑ "Constitution". The National Gallery. http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/constitution/. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ Gentili 2000, 7

- ↑ Chilvers, Ian (2003). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford Oxford University Press, p. 413. The formula was used by Michael Levey, later the Gallery's eleventh director, for the title of a popular survey of European painting: Levey, Michael (1972). From Giotto to Cézanne: A Concise History of Painting. London: Thames and Hudson

- ↑ Potterton 1977, 8

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Taylor 1999, 29–30

- ↑ Moore, Andrew (2 October 1996). "Sir Robert Walpole's pictures in Russia". Magazine Antiques. http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1026/is_n4_v150/ai_18850830/pg_2. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ↑ Penny 2008, 466

- ↑ Fullerton, Peter (1979). Some aspects of the early years of the British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom 1805–1825. MA dissertation, Courtauld Institute of Art., p. 37

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 45

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 51

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Taylor 1999, 36–7

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 'Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery', Survey of London: volume 20: St Martin-in-the-Fields, pt III: Trafalgar Square & Neighbourhood (1940), pp. 15–18. Date accessed: 15 December 2009.

- ↑ MacGregor, Neil (2004). "A Pentecost in Trafalgar Square", pp. 27–49 in Cuno, James (ed.). Whose Muse? Art Museums and the Public Trust. Princeton: Princeton University Press and Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, p.30

- ↑ Quoted in Langmuir 2005, 11

- ↑ Robertson, David (2004). "Eastlake, Sir Charles Lock (1793–1865)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Grove Dictionary of Art, Vol. 9, p. 683

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Baker, Christopher and Henry, Tom (2001). "A short history of the National Gallery" in The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue. London: National Gallery Company, pp. x–xix

- ↑ NG London/Turner Bequest. Retrieved on 11 January 2009

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 107

- ↑ The Mond Bequest (Official NG website)

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 132

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 134

- ↑ Spalding 1998, 39

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 131

- ↑ Bosman 2008, 25

- ↑ MacGregor, op. cit., p.43

- ↑ Bosman 2008, 79

- ↑ Bosman 2008, 35

- ↑ Bosman 2008, 91–3

- ↑ Bosman 2008, 99

- ↑ "Sir Denis Mahon". Cronaca. 2003-02-23. http://www.cronaca.com/archives/000503.html. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Gaskell 2000, 179–182

- ↑ Bailey, Martin (2 November 2005). "National Gallery may start acquiring 20th-century art". The Art Newspaper. http://www.theartnewspaper.com/article01.asp?id=55. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ↑ Gayford, Martin (23 April 2007). "Wanted – National Gallery Chief to Muster Cash". Bloomberg.com. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601088&sid=alG6uNHZGr3M&refer=muse. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Liscombe 1980, 180–82

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Summerson 1962, 208–9. Summerson's "mantelpiece" comparison inspired the title of Conlin's 2006 history of the Gallery, The Nation's Mantelpiece (op. cit.).

- ↑ Grove Dictionary of Art, Vol. 33, p. 192

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 60

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 367

- ↑ Quoted in Tyack, Geoffrey (1990). "'A Gallery Worthy of the British People': James Pennethorne's Designs for the National Gallery, 1845-1867", pp. 120–134 in Architectural History, Vol. 33, 1990, p. 120

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 384-5

- ↑ Barker 1982, 116–7

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 396

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 399

- ↑ Conlin 2006, 404–5

- ↑ Oliver 2004, 54

- ↑ See for example National Gallery (corporate author) (1974). The Working of the National Gallery. London: National Gallery Publishing, p. 8: "the National Gallery has suffered from the visual pretentiousness of its 19th century buildings". The modernist North Galleries opened the following year.

- ↑ They were restored only in 2005. Jury, Louise (14 June 2004). "A Victorian masterpiece emerges from beneath the whitewash". The Independent. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4158/is_20040614/ai_n12791111. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ↑ "A speech by HRH The Prince of Wales at the 150th anniversary of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), Royal Gala Evening at Hampton Court Palace". http://www.princeofwales.gov.uk/speechesandarticles/a_speech_by_hrh_the_prince_of_wales_at_the_150th_anniversary_1876801621.html. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ↑ "Prince's new architecture blast". BBC News. 2005-02-21. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/4285069.stm. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ↑ "No cash for 'highest slum'". BBC News. 2001-02-09. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/1162818.stm. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ↑ Bomford 1997, 72

- ↑ Bomford 1997, 7

- ↑ Walden 2004, 176

- ↑ "AfterRubens.org: The Strange Story of the Samson and Delilah". http://www.afterrubens.org/home.asp.

Bibliography

- Barker, Felix; Hyde, Ralph (1982), London As It Might Have Been, London: John Murray

- Bomford, David (1997), Conservation of Paintings, London: National Gallery Company

- Bosman, Suzanne (2008), The National Gallery in Wartime, London: National Gallery Company

- Conlin, Jonathan (2006), The Nation's Mantelpiece: A History of the National Gallery, London: Pallas Athene

- Gaskell, Ivan (2000), Vermeer's Wager: Speculations on Art History, Theory and Art Museums, London: Reaktion

- Gentili, Augusto; Barcham, William; Whiteley, Linda (2000), Paintings in the National Gallery, London: Little, Brown & Co.

- Jencks, Charles (1991), Post-Modern Triumphs in London, London and New York: Academy Editions, St. Martin's Press

- Langmuir, Erika (2005), The National Gallery Companion Guide, London and New Haven: Yale University Press

- Liscombe, R. W. (1980), William Wilkins, 1778–1839, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Oliver, Lois (2004), Boris Anrep: The National Gallery Mosaics, London: National Gallery Company

- Penny, Nicholas (2008), National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings, Volume II, Venice 1540–1600, London: National Gallery Publications Ltd, ISBN 1857099133

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Bradley, Simon (2003), The Buildings of England London 6: Westminster, London and New Haven: Yale University Press

- Potterton, Homan (1977), The National Gallery, London, London: Thames & Hudson

- Smith, Charles Saumarez (2009), The National Gallery: A Short History, London: Frances Lincoln Limited

- Spalding, Frances (1998), The Tate: A History, London: Tate Gallery Publishing

- Summerson, John (1962), Georgian London, London: Penguin

- Taylor, Brandon (1999), Art for the Nation: Exhibitions and the London Public, 1747–2001, Manchester: Manchester University Press

- Walden, Sarah (2004), The Ravished Image: An Introduction to the Art of Picture Restoration & Its Risks, London: Gibson Square

- Whitehead, Christopher (2005), The Public Art Museum in Nineteenth Century Britain, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing

External links

- Official website

- National Gallery elevation

- The Building of the National Gallery

- 360° panoramas of 17 rooms in the National Gallery

- 360° panoramas of the Staircase Hall, Sainsbury Wing, Barry Octagon, Annenburg Court and basement

- The National Gallery at Pall Mall from The Survey of London

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

,_British_Portraits_1750-1800_~_The_Barry_Rooms_+_View_to_RM37.3.jpg)